BLOG: Place-making and health: what does 'good' look like?

Third-year Masters in Public Health online student, Yvonne Kerr, reflects on place and placemaking's health impacts, highlighting community engagement.

By Yvonne Kerr | Third-Year MPH Student

I began this piece of work by asking what felt like pretty big questions:

- What do we mean when we talk about 'place' and 'placemaking' - and why are these important concepts for health, and for Public Health?

- Is there a shared understanding of these terms amongst decision makers and why they are so important to health?

- How do we involve local communities in their 'place', ensuring their voices are heard and their ideas acted upon - how do we support people to feel a part of their 'place' and why does this matter?

By asking these questions I have taken myself on quite a learning journey, both professionally and personally.

What do these terms mean? The definitions below are provided by the Scottish Government.1

- Placemaking

- Placemaking refers to the environment in which we live; the people that inhabit these spaces; and the quality of life that comes from the interaction of people and their surroundings. Placemaking is dependent on a collaborative approach involving the design and development of places over time with people and communities central to the process.

- Place

- Place refers to the built and natural environment and is informed by policy, legislation and evidence about (but not confined to) spatial planning, transport, housing, greenspace, education and community empowerment.

In general, people have a fairly strong sense of their local ‘place’ – good or bad. What is important regarding a place, particularly when talking about where we live, changes as our circumstances change, for example, if we have children or not.

There is a good understanding of the practical impacts of place on general health and wellbeing. People understand that to be healthy we need good quality housing, safe streets, access to green spaces and so on. What becomes more difficult for people to express is how place contributes to our emotional and social health and wellbeing. It’s not just about feeling safe, it’s about feeling welcome, involved, listened to and valued. Very interesting conversations around this were had with young people, people who are transgender, people who have a disability – essentially those who feel very ‘seen’ in their local place, and not always for what feels like positive reasons.

When it comes to decision makers and planners, the link between the work they do, for example, in designing and building new housing estates, and how this impacts on health and wellbeing is clear in parts, but could be improved. It’s more than just making sure there are enough primary school places and a health centre – much more is needed if people are to really feel like the place in which they live, work and socialise is supporting them to fulfil their potential.

Local communities have a lot to say about their 'place', but some voices are excluded from this narrative. My SLICC (Student-Led, Individually-Created Course) project focused on engaging with children and young people, working alongside an organisation to support them to develop their own community maps, outlining what they liked and wanted improved in their local area.

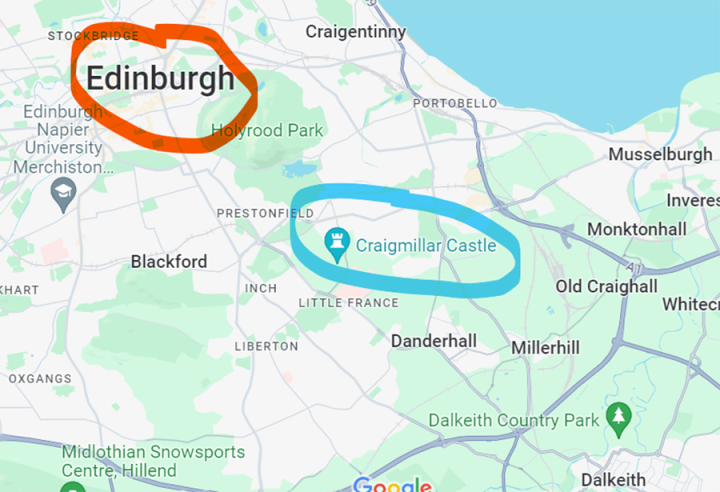

This was a real eye-opener for me and a part of the process I very much enjoyed. This took place in Craigmillar, an area of Edinburgh located to the South East of the city centre. Craigmillar is a deprived part of the city, which brings with it various challenges, and due to this I was expecting to hear a lot of negativity.

The map shown on the right outlines the location of Craigmillar (blue) and its proximity to the city centre (red).2

Although issues were flagged that were less than positive, there was a lot about their local community that these children and young people were very proud of – a useful reminder that 'place' means more than what you see by looking at things like deprivation data.

From these, key actions have been identified and a group of stakeholders developed to make sure these are taken forward. This includes health, local authority, third sector and (critically) the people who live in this part of the city and who will be directly impacted upon by any decisions made. By doing this we can work together to make sure that when it comes to place and its' impact upon health, it does indeed look ‘good’ and that the version of good fits with the needs and issues identified by local communities themselves.