The sky’s no limit

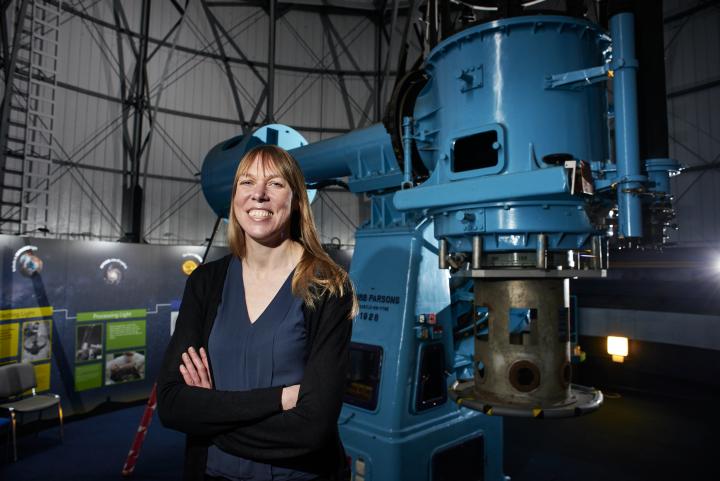

As the first female Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Professor Catherine Heymans is on a mission to lift our eyes to the marvels of the universe.

“Utterly breathtaking,” is how Professor Catherine Heymans describes it.

“I don’t think anyone ever forgets the first time they saw the rings of Saturn through a telescope, but too many people never have the chance,” she says. “I want to help change that.”

Professor Heymans is reflecting upon her appointment as the 11th Astronomer Royal for Scotland. In doing so, she becomes the first woman to hold the prestigious position in its almost 200-year history.

Her vision for the role is to promote Scotland internationally as a world-leading centre for science, and to share her passion and enthusiasm for astronomy with people from all walks of life, especially children and young people.

“I’ve witnessed first-hand the wonderful transformation in children when they see the craters of the Moon or Saturn’s rings with their own eyes,” she says. “My hope is that once a spark and connection with the universe is made, children will carry that excitement home with them and develop a life-long passion for astronomy or, even better, science as a whole.”

Full orbit

Professor Heymans speaks with the energy and enthusiasm you might expect from someone who helped pay their way through university by working as a tour guide at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

Now, in a way, she has come full circle, or, if you will, completed a full orbit. Created in 1834, the position of Astronomer Royal for Scotland was originally held by the observatory’s director. Since 1995, however, it has been awarded as an honorary title. The previous holder, Professor John C Brown, passed away in 2019.

Heymans is Professor of Astrophysics in the University’s School of Physics & Astronomy and Director of the German Centre for Cosmological Lensing at Ruhr-University Bochum. With more than 185 articles in scientific journals to her name, Professor Heymans is internationally recognised as a leading expert on the physics of the so-called dark universe.

Her research seeks to shed light on the mysteries of dark energy and dark matter – elusive entities that together account for more than 95 per cent of the Universe. It’s a stunningly complex area of research that draws on every aspect of physics to try to make sense of the extraordinary, cataclysmic events that formed, and continue to shape, our universe.

As Professor Heymans puts it, it’s the biggest puzzle in science at the moment: “The fundamental laws of physics don’t make sense based on the observations that we’re making. So, that means we’ve got something very wrong.”

Extra dimensions, multiple universes or something akin to a second – much slower – Big Bang are some of the possible explanations. It may sound like the stuff of science fiction, but a better understanding of them could help astrophysicists like Professor Heymans provide meaningful answers to a perennial question that’s been asked since the dawn of humanity: why are we here?

“It could be that we’re here simply because we’re in a universe that allows us to be here, and that there are infinite other universes out there with no humans,” says Professor Heymans. “Our universe may just happen to be a strange, freak version of the average universe.”

This is what’s known as multiverse theory: the idea that there are multiple universes in existence, and that they are being created endlessly in space and time. When things are duplicated over and over again, they can develop slight differences.

“Just as there are billions of people in the world who differ from each other in all sorts of ways like height, weight and eye colour, it could be that a similar thing happens with universes,” says Professor Heymans. “Maybe our universe is like the eight-foot-tall basketball player.”

Classroom to cosmos

Grappling with such transcendent, bewildering concepts, and challenging the theories of Albert Einstein would be a daunting prospect for most people, but from an early age Professor Heymans has always been up for a challenge.

At the age of six, she asked her teacher what the hardest job in the world was. Their answer: astrophysicist or brain surgeon. In the end, it was as a teenager that Heymans made up her mind that brain surgery wasn’t for her, a decision she says was largely down to having a great physics teacher.

Recognising the influence that her own experiences in the classroom had on her decision to become an astrophysicist, Professor Heymans is working on ways of using her new position as Astronomer Royal for Scotland to help support teachers.

She says: “In my view, just about every academic will tell you that behind their passion for their particular subject has been an amazing teacher. On top of that, after home-schooling my own children for eight months, it’s abundantly clear to me that teachers really are amazing, so I want to do all that I can to help support the incredibly important work they do.”

Space for all

As well as engaging with teachers across Scotland, Professor Heymans is eager to connect with the country’s amateur astronomers, and further her participation in science policy and advisor roles.

Ultimately, it’s all about trying to bring astronomy to as wide an audience as possible, says Professor Heymans: “It’s very hard for young people to see themselves going on to be a scientist or an astronomer when they grow up when virtually everyone they see doing that doesn’t look like them.

“As an advocate for equality and diversity, it is a great honour to be the first woman appointed as Astronomer Royal for Scotland, and my hope is that children across Scotland and the UK can see me as a role model, and that that can help inspire them to pursue their dreams.

“There’s still a huge amount that must be done to address issues of underrepresentation in science, particularly for women and people of colour, but I’m hopeful that this a positive sign that things really are beginning to change.”

Find out more

Writer: Corin Campbell

Photography: Maverick Photo Agency, ESA/Hubble & NASA – acknowledgement Judy Schmidt.