Thought without learning is perilous

The University of Edinburgh has a uniquely strong relationship with China. Edd McCracken explores the continuing work to deepen mutual understanding between our two cultures.

January is not Edinburgh’s kindest month. After the Christmas lights and Hogmanay fireworks, the season can appear a little grey. Last January, however, the University’s Old College quadrangle held the winter gloom at bay thanks to a uniquely Chinese intervention.

More than 70 lanterns in the shape of China’s famous Terracotta Warriors illuminated the quad. Standing in formation and most measuring more than two metres high, the figures cast yellow, blue, green and red light onto Old College’s walls.

Designed by artist Xia Nan for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the exhibition marked the Chinese New Year in Edinburgh. Images of the luminous army were beamed around the world, including back to China.

More than 30,000 visitors came to see the magical display in its 10-day run. It was the most popular event ever held in the quadrangle.

“What was beautiful about the event was that it was contemporary, cutting edge art but using a classical topic,” says Professor Natascha Gentz, Director of the Confucius Institute for Scotland in the University of Edinburgh and one of the key figures in the lanterns’ installation. “You had both sides of China in one exhibition.”

This was not the first time China has been at the heart of the University. It is a relationship and story that stretches back centuries.

In 1855 Huang Kuan graduated in medicine from the University. He was the first Chinese student to study in the West, and took new medical techniques back to Asia. Since then the relationship between Edinburgh and China has weathered huge political change, but continues to be pioneering.

In 2007 Scotland’s first Confucius Institute opened at the University. It has since been named Confucius Institute of the Year six times by Hanban, the Chinese cultural agency that oversees more than 500 institutes globally.

Academic and research partnerships and exchanges, particularly in the areas of science, engineering and medicine, are flourishing.

“It is a very important relationship,” says Professor James Smith, Vice-Principal International. “You can play a role in all sorts of things through a relationship with China. It is significant geopolitically and increasingly economically. Of all the regions in the world, China is one of the most important.”

What we’re trying to achieve is for people to get a sense of why China does things the way it does.

With the world’s economic health tethered to that of China’s, and the scenes of protest on the streets of Hong Kong in autumn 2014, China is a country that demands to be understood. The University is playing a role in this dialogue. “What we’re trying to achieve is for people to get a sense of why China does things the way it does,” explains Professor Gentz. “In the press or public speeches there is very quickly a condemnation. But if you study China, spend time in China, you can see its internal reasons, the challenges it has, and why it reacts this way. This does not mean one has to agree with everything, but there is no point in lecturing China.

“I would want people to be more knowledgeable about China. We want people to engage with China. So that’s what we’re trying to do with these events.”

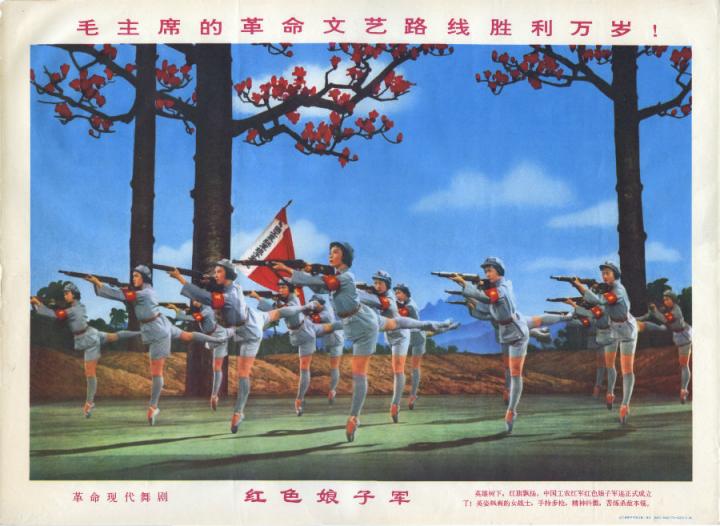

Events such as the hugely successful exhibition of modern Chinese poster art. More than 5,000 people visited the University’s Adam House in June and July to see colourful populist images from 1913 to 1997. It was the largest such exhibition shown outside of China.

The images came from the Propaganda Poster Art Centre in Shanghai. Once an underground gallery, the centre is now partially funded by the Chinese government.

Low cost and accessibility made posters a ubiquitous art form in 20th century China. The Edinburgh exhibition was a pictorial history of a tumultuous age, from glamorous women advertising perfume in the republican 1930s to the ever-present Little Red Book and beaming face of Chairman Mao after the Communist Party’s triumph in the 1940s.

“When we think about propaganda posters we have a very clear image of things like the Cultural Revolution posters, which are very stereotyped and violent,” says Professor Gentz. “But there is a broad range and diversity of posters, which is why we put this exhibition on. ”

Nearly 160 years after Huang Kuan made his arduous trip to Scotland, the University is home to more than 2,000 Chinese students. In 2013/14, more students joined the University from China than from the USA.

“The first day I was really surprised,” says Liming Jiang, a fourth-year PhD student from Shanghai and member of the Edinburgh Chinese Scholar and Student Association. “I was walking across the Meadows and I saw a lot of Chinese students – a lot of familiar faces.”

Mr Jiang’s tale is a familiar one. He came to Edinburgh following the recommendations of his professors at Tongji University in Shanghai and visiting Edinburgh academics.

“For Chinese students London and Edinburgh are the two cities they are interested in,” he says. “It’s definitely a welcoming place. The Chinese students really like Scottish culture. Scots are very hospitable, and Edinburgh is a wonderful place to study. I appreciate every day that I am here.”

Ni Hao and Happy Birthday

Ten-year celebrations

A pop-up Chinese tea house helped transform the Mound in central Edinburgh as the University’s Confucius Institute for Scotland joined celebrations to mark 10 years of the global Confucius Institute project, in late September.

There were stage performances throughout the day showcasing Chinese pop and classical music and dance, and storytelling by the award-winning Rickshaw Theatre. Members of the public enjoyed Tai Chi sessions, learnt basic Chinese phrases, and left messages of hope on a traditional wishing tree.

Visitors could try their hand at Chinese calligraphy, play traditional string and wind instruments, or sample a range of Chinese teas. With two larger-than-life panda mascots on hand, the event was difficult to miss.

The Confucius Institute for Scotland was opened in 2007 at Arden House, next to the Pollock Halls student accommodation. It is one of more than 500 Confucius Institutes across the world, established by Hanban, the Chinese government department responsible for promoting Chinese culture and language overseas. It has been named as among the best such Institutes in the world six times since its establishment.

Title quote is from Confucius