Satellite observations reveal that 71 of Antarctica’s 162 ice sheets thinned between 1997 and 2021, leading to an extra 7.5 trillion tonnes of meltwater in the oceans.

The findings show all the ice shelves on the western side of Antarctica – which is exposed to warmer waters than the rest of the continent – lost ice, while most on the eastern side stayed the same or got bigger.

The study, led by the University of Leeds, involved a researcher from Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences and University start-up Earthwave.

Plugging losses

Almost 67 trillion tonnes of ice was lost over the 25-year period. This was offset by 59 trillion tonnes of ice being added to some ice shelves, giving a net loss of 7.5 trillion tonnes.

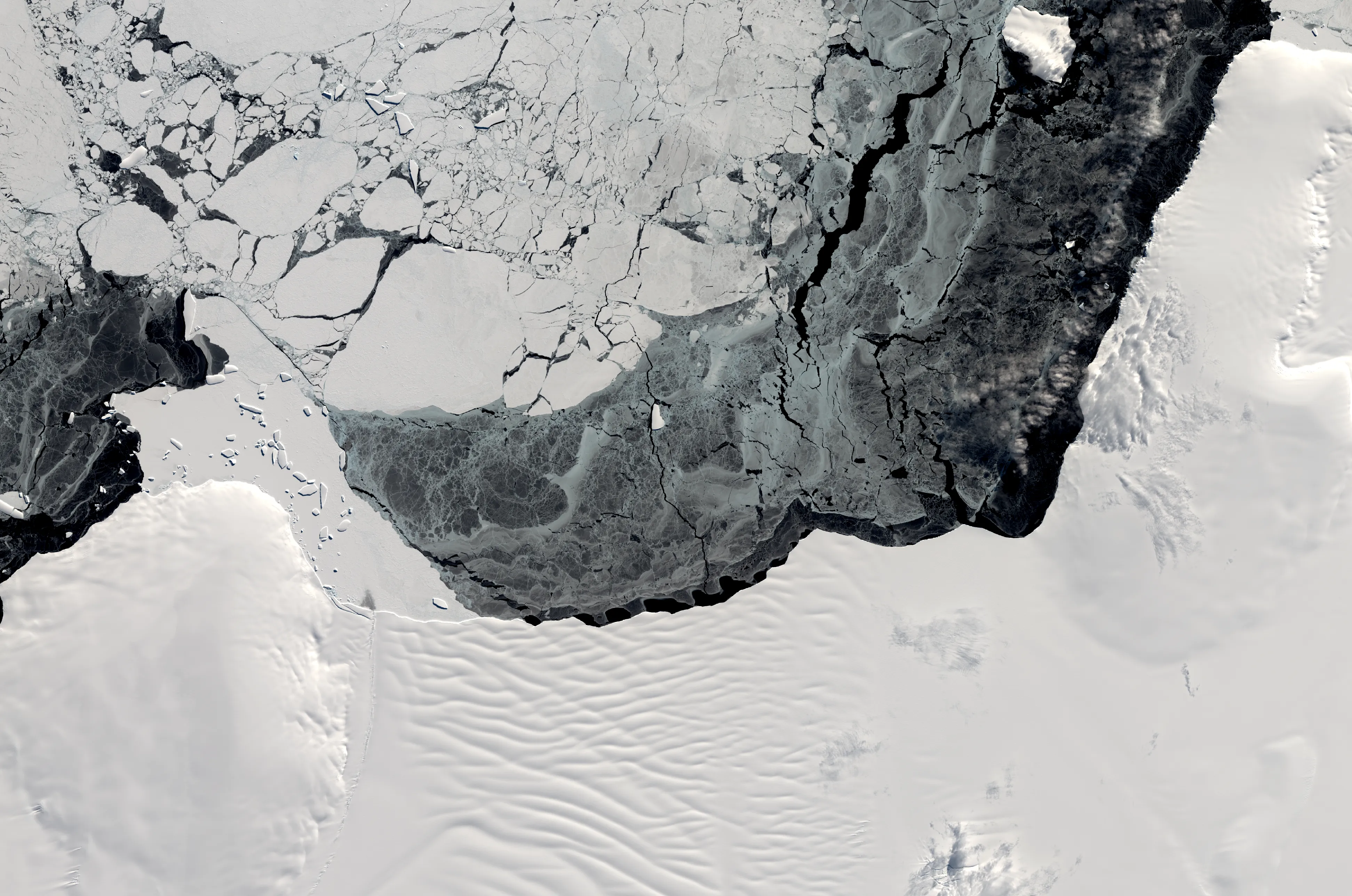

Floating ice shelves – extensions of the ice sheet that covers much of Antarctica – act like giant plugs at the end of glaciers, slowing the flow of ice into the oceans. This plugging effect is weakened when ice shelves get smaller, increasing the rate of ice loss from glaciers.

Human-induced global warming is likely to be a key factor in the loss of ice, the team says. If it was due to natural climate variation, they would have seen signs of ice regrowth on western ice shelves.

Ice changes

Some of the biggest losses over the 25-year period were on the Getz Ice Shelf, where 1.9 trillion tonnes of ice were lost. Just 5 per cent was due to calving – where large chunks of ice break away from the shelf and move into the ocean – with the rest caused by melting at the base of the ice shelf.

Similarly, on the Pine Island Ice Shelf, 1.3 trillion tonnes of ice were lost. Around a third of that loss was due to calving, with the rest due to melting from the underside of the ice shelf.

In contrast, the Amery Ice Shelf – on the eastern side of Antarctica – gained 1.2 trillion tonnes of ice.

Satellite images

Researchers analysed more than 100,000 satellite radar images to study changes to Antarctica’s ice shelves since 1997. Data in recent years has come largely from the CryoSat-2 and Sentinel-1 satellites.

CryoSat-2 has been an incredible tool for monitoring the polar environment. Its ability to precisely map the erosion of ice shelves by the ocean below enabled this accurate quantification and partitioning of ice shelf loss, but also revealed fascinating details on how this erosion takes place.

Professor Noel Gourmelen

School of GeoSciences

Knock-on effects

The collapse of Antarctica’s ice shelves could affect millions of people living in low-lying communities around the world due to rising sea levels.

Loss or reduction in the size of ice shelves could also have knock-on effects for the global ocean circulation system, which transports nutrients, heat and carbon around the world, the team says.

Freshwater from Antarctica’s ice shelves dilutes the dense, salty ocean water and makes it lighter, which means it takes longer to sink to the ocean floor. This can weaken the circulation system, as it is driven partly by the movement of dense water in the deep sea, the researchers say.

The research is published in the journal Science Advances. It was supported by the European Space Agency, European Commission, Natural Environment Research Council and the UK Earth Observation Climate Information Service.

We tend to think of ice shelves as going through cyclical advances and retreats. Instead, we are seeing a steady attrition due to melting and calving. Many of the ice shelves have deteriorated a lot: 48 lost more than 30 per cent of their initial mass over just 25 years. This is further evidence that Antarctica is changing because the climate is warming. The study provides a baseline measure from which we can see further changes that may emerge as the climate gets warmer.

Professor Anna Hogg

University of Leeds