Malaria immunity insight could lead to new vaccine development

Key insights on how malaria immunity develops after repeated infections could lead to new vaccine strategies and change the approach to tackling other infectious diseases, a study has found.

The findings overturn thinking on how immunity to malaria develops, revealing that the immune system prioritises damage limitation rather than killing parasites when re-exposed to the infection.

Understanding how the immune system limits the damage the infection causes, rather than attempting to get rid of the parasites, could double the number of potential malaria vaccine options.

Malaria Vaccines

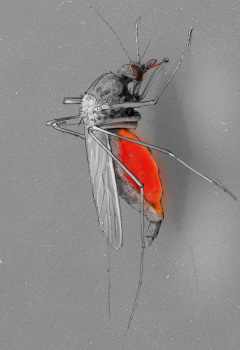

Malaria is spread by mosquitoes and kills around half a million people every year before they have had time to acquire immunity to the disease.

Deaths from severe malaria are most common during the first infection, meaning that children are at most risk and account for nearly 70% of all malaria deaths worldwide.

Despite decades of research, current malaria vaccines offer less than 30% protection for children under five, leaving the majority of this most vulnerable age group at risk.

Developing Immunity

It takes many years for the immune system to learn how to kill malaria parasites, yet previous research has shown that children who survive their first infection quickly develop immunity against severe forms of the disease.

When people are re-infected with malaria they often experience milder symptoms compared to their first infection, even if they have the same or greater numbers of parasites in their body.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh carried out studies in mice to compare the immune response during repeated malaria infections, to better understand how immunity to severe disease develops.

Damage Limitation

The study found that during the first infection the immune system’s cells trigger inflammatory processes in an attempt to kill the malaria parasites.

However, this response is unsuccessful and damages blood vessels causing life-threatening symptoms.

In contrast when mice are re-infected the same immune cells switch to damage limitation, restricting the inflammatory response to keep blood vessels healthy and reduce disease severity.

Learning to dampen the inflammatory response reduces the risk of death, buying the time needed to learn how to fight the parasites over a longer period of time.

The lead author of the study, Dr Wiebke Nahrendorf from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Biological Sciences, said:

There are two parts to immunity against malaria: learning to survive infection is the priority – there’s no point triggering an immune response that tries to get rid of the parasites if you end up killing yourself in the process. So you need to change tack pretty quickly! Learn to tolerate infection and you can then take your time to work out how best to kill the parasites.

The study concludes that a single infection is enough to trigger long-term protection against severe malaria.

Tolerating Infections

Immune cells remember to ‘tolerate’ future infections, even when they have previously been treated with drugs that kill malaria parasites.

The ability to tolerate infection develops because the spleen, the organ which helps to control the immune response, is permanently altered by malaria and reprograms immune cells to promote tissue healing.

Infectious disease research usually focuses on strategies that kill parasites and other disease-causing microbes. Yet this study reveals that developing ‘tolerance’ is an equally effective tactic.

Understanding how the immune system learns to ‘remember’ previous infections and build this tolerance, even years after the initial infection, could lead to new strategies to tackle other diseases.

Dr Phil Spence, who oversaw the project at the University of Edinburgh, said:

We often think of immunity to malaria as slow to develop and ineffective. But it does exactly what it is supposed to do - it prioritises host fitness over pathogen clearance. If we understand how you learn to tolerate infection we can protect the most vulnerable.

The study, supported by the Wellcome Trust and Royal Society, was published in eLife.