The study marks the first time the genetic risk for haemochromatosis – also known as the ‘Celtic curse’ – has been mapped across the UK and Ireland, despite a high incidence of the condition among Scottish and Irish populations.

Targeting genetic screening for the condition to priority areas could help identify at-risk individuals earlier and avoid future health complications, experts say.

Genetic risk

Haemochromatosis symptoms can evolve over decades as high iron levels in the body cause damage to organs. Early diagnosis and treatment – such as regular blood donation to reduce iron levels – is key to prevent liver damage, liver cancer and arthritis.

The condition is caused by small changes in DNA, known as genetic variants, which can be passed down through families. The most important risk factor in the UK and Ireland is a genetic variant called C282Y.

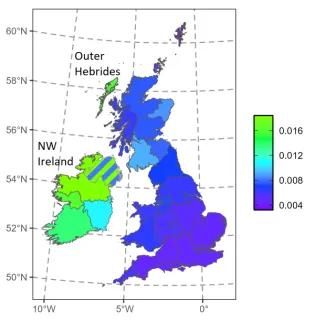

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh analysed genetic data from more than 400,000 individuals in the UK BioBank and Viking Genes studies to determine the prevalence of the C282Y variant across 29 regions of the British Isles and Ireland.

Celtic connection

They found that people with ancestry from the north-west of Ireland have the highest risk of developing haemochromatosis, with one in 54 people estimated to carry the genetic variant. This is followed by Outer Hebrideans (one in 62) and those from Northern Ireland (one in 71).

Mainland Scots – particularly in Glasgow and southwest Scotland – are also at increased risk of the condition, with one in 117 people estimated to carry the variant, corroborating the ‘Celtic Curse’ nickname.

The high combined genetic risk across these locations suggests that focusing genetic screening at these key areas would discover the largest number of people with the condition, researchers say.