Dr Joana Alves on bacterial infections

Understanding superbugs, using a board game for public engagement and cutting plastic use in labs

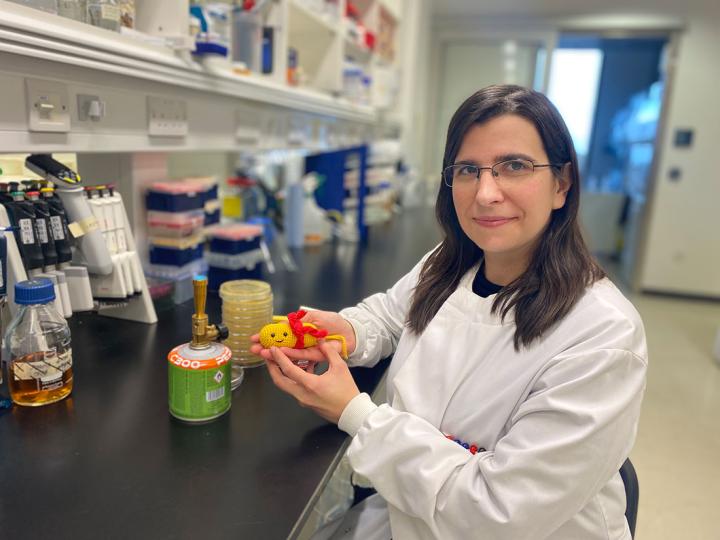

Dr Joana Alves is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Roslin Institute, where she studies the interaction between bacteria and the people they infect. In this interview, she talks to MSc Science Communication student Yee Theng Soo about her research and life as a scientist.

Can you tell me about your work in a nutshell?

I conduct research into bacteria. One of my projects looks at Staphylococcus aureus, which is known as a superbug because it can be resistant to many antibiotics. I am trying to understand how these bacteria hide from our immune cells, and to identify the genes or parts of the bacteria that enable them to infect us.

I am also working on Legionella pneumophila, a bacteria that causes a serious lung infection called Legionnaires’ disease in humans, looking at the different strains of the bacteria to figure out why some cause infections while others do not.

This knowledge could be useful in the development of therapies and vaccines against these bacteria.

What inspired you to follow this career path?

In high school, I loved studying science, mathematics, physics and chemistry. I decided to pursue biochemistry, which led to my first experience working in a science lab. Spending time in the lab during my undergraduate and master’s degrees led me to realise that research is definitely something I see myself doing. This realisation kickstarted my career.

I moved on to do a PhD specialising in infections in new-borns. While I was looking for a postdoc position, I came across an interesting project at the Roslin Institute that aligned with my skillset and provided many opportunities for learning, and that is how I got here.

Do you engage the public with your research?

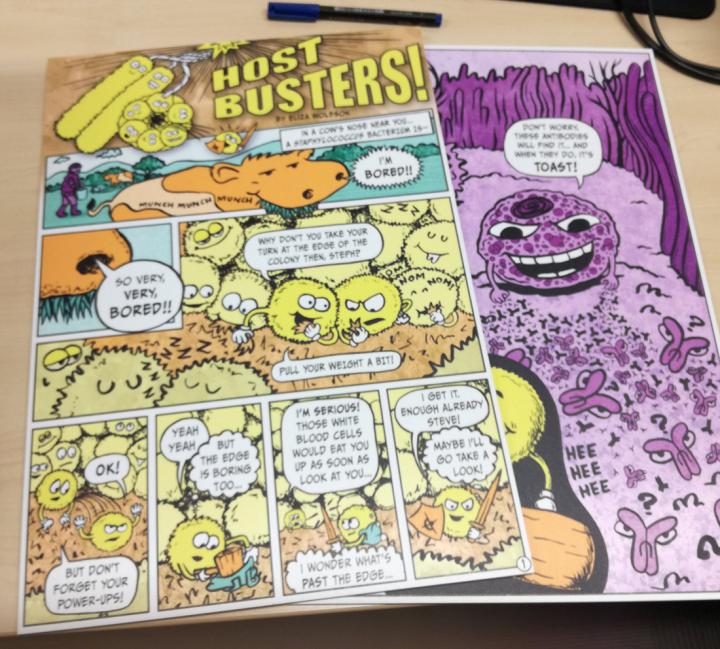

I am involved in the development of a public engagement activity called ‘Hostbusters’, and I am really proud of it. Together with my colleagues, we wanted to come up with an activity to explain how bacteria travel from one animal or person to another, so we decided to create a board game. We also made a comic book that describes the backstory of the game.

Briefly, a bacteria living in the nose of a cow wanted to do more exciting things by traveling to other individuals, or hosts. Players are the bacteria and need to infect as many hosts as possible to win. It is a nice way to introduce the concepts of mutation and gene transfer. It is a fun and challenging game that works very well with both kids and adults.

You worked with a colleague to cut plastic use in the lab. How did you do it?

I started this initiative with my colleague Dr Amy Pickering. We measured our lab’s plastic waste before and after implementing a series of plastic-reducing strategies. For example, we were able to replace several single-use plastic items with metal, glass and wood alternatives that can be re-used. We also created a decontamination station that allowed us to decontaminate, wash, sterilize and re-use plastic tubes, which are one of the main single-use plastic item in most labs.

Changing the way we do experiments is also useful. In our microbiology lab, a lot of petri dishes are used to cultivate bacteria. We showed colleagues different ways of working to reduce the number of petri dishes used without compromising results. This allowed us to save plastic and time.

We calculated that our approach could cut the amount of plastic discarded in a lab by 500kg a year and we saved more than £400 in the first three months.

We are also in the process of acquiring funding to buy glass equipment to replace plastic.

What do you love most about what you do?

I love the constant learning that comes with my work. Life as a researcher is not monotonous. Even though some tasks are repetitive such as growing bacteria and counting plates, the question I am trying to answer is almost never the same. It is like having a new puzzle to solve every single week. I find that really fascinating and exciting.

What are the challenges you face as a scientist?

I think the biggest challenge is balancing my time. Especially now that I am a recent mother, I need to balance my time in a different way and learn to define priorities.

I am also constantly reflecting on my personal and professional values, which are not necessarily associated with each other. For example, not all experiments will work out according to plan. I am trying to learn and accept the fact that my failed experiments do not reflect my worth as a scientist.

If you could do anything without money and time constraint for your work, what would it be?

I would like to explore microscopy more. I love seeing other researchers’ photos of their bacteria taken with a lot of colours and fluorescence. I have always wanted to make nice videos and photos of my work – I could even display them in my office and show people the bacteria I am working on. Even though we know how bacteria function, seeing them in action under the microscope is amazing.

What would you be doing if you were not a scientist?

I would probably be teaching. I love teaching, it is one of my favourite things to do. I like the challenge of explaining the most complex subjects as simple and exciting as possible. I used to give a few lectures back when I was doing my PhD and now I have the opportunity to teach Master and PhD students in the lab about research, scientific methods and lab techniques. It is fulfilling to directly contribute to someone’s scientific knowledge and success.

Do you have any message for students who are interested in doing what you do?

One piece of advice that I would have loved to receive when I was younger is to not be afraid of getting in touch with scientists if you would like to do an internship or placement. I find that most scientists are very keen to teach and share their knowledge.

Another aspect to consider is that academia involves more than doing lab work. It also requires other skills such as networking, public speaking, writing and public engagement.

Related links

Sustainable lab scheme cuts plastic waste and costs