Dr Finn Grey on the genetics of virology

The genetics of viruses and the people and animals they infect, and 42 years waiting to be part of the Scottish football team.

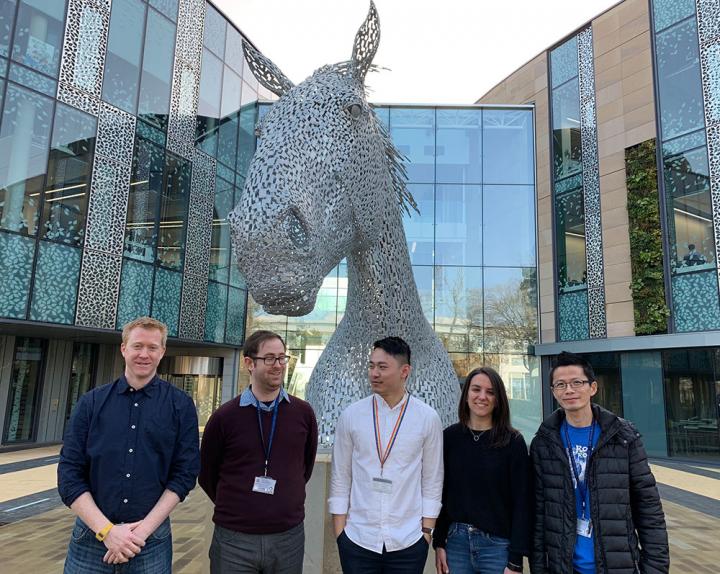

Finn Grey is a senior group leader at the Roslin Institute with over fifteen years of experience in Virology. In this interview, he tells science communication student Alex Bradie about his work in understanding how pathogens interact with their hosts.

Could you describe your work in a nutshell?

The main focus of my research is understanding how pathogens such as viruses interact with the people and animals they infect on the cellular level.

The main idea is to understand which host genes are particularly important for the pathogens. You can break it down into three main parts: 1) how the pathogen interacts or manipulates host cells, 2) how the host responds to the pathogen - how it sets up defences to block the pathogen from replicating, and 3) how the pathogen has evolved to counteract those defence mechanisms.

How did you become interested in this field of research?

The main area of interest I took from my undergraduate was virology because it had a medical relevance. Viruses are kind of cool and it’s an interesting area, so I was drawn to it and ended up doing a PhD in virology.

What are some real-world applications of your research?

The main virus I work on is Human Cytomegalovirus Virus (HCMV) which is a herpes virus. We are interested in the basic biology but, through that, we can have findings that have clinical relevance.

We also work in the area of livestock research, on livestock viruses. The idea is that we take the expertise we’ve used in HCMV and transfer it over to livestock. There are very few tools available for livestock research, so there was a big gap that needed filling.

Humans aren’t the only species that get the flu. Pigs and chickens also get it and the flow of virus from these animals to humans underpins the potential for pandemic outbreaks. We have been developing gene libraries for these animals so that we can start investigating their genetic makeup to see which genes are important and then compare them with humans.

The other aspect of the research which we’ve started doing focuses specifically on the interferon response, which is the first barrier to a viral infection. If you treat cells with interferon they become resistant to viral infection but how this happens is not clear. One of the reasons it’s hard to figure this out is that when you become infected with a virus you upregulate over 500 genes and trying to find out which ones are important for different viruses is difficult.

We’ve just recently got a grant to generate interferon stimulated gene (ISG) libraries for pigs and chickens, asking questions about influenza – the virus sometimes jumps from pigs and chickens to humans, but this is a rare event. One of the questions we’re trying to answer is why is this so rare? Why is it difficult for the virus to jump across?

What challenges do you come across in your research?

That it doesn’t work! A lot! That’s hard and it’s slow. I’m not the most patient person, I think other people may be better adapted or have characteristics where they enjoy the process of getting to the answer. I’m not like that – I just want to get the data and for it to have worked, and a lot of the time it doesn’t and I find that quite frustrating.

At the moment there is constant pressure to get funding, it almost seems like the further along in your career you go, the harder it gets because you’re not relying on other people, you’ve got to get it yourself.

Why did you become a scientist?

I didn’t enjoy primary school at all – to me there was just a lot of English and maths which were not my favourite subjects – so much long division! But when I went to high school, the programme was divided up into subjects. I remember getting my first timetable: “these are your subjects, these are the classes you’re going to”. I remember seeing science and thinking “that’s going to be cool” and I guess it just went on from there!

If you weren’t a scientist, what would you be?

A professional footballer – I’m still waiting on the call! I mean, the bar for the Scottish national team is not that high so maybe it will still happen at the young age of 42! It’s unlikely though. I think instead I’ll put a huge amount of pressure on my son and daughter so I can live my dreams through them – they will not enjoy that!

Related links

Gene study set to investigate how flu jumps species

Gene-edited chicken cells resist bird flu virus