Thymus cell study sheds light on immune ageing

Collaborative single cell study suggests disruption to thymic progenitor differentiation contributes to ageing related immune impairment : August 2020

"Why does our immune system become less effective as we age?" is a question that has inspired many biomedical scientists. The thymus is a key immune organ which is the main site for the training of T cells, vital to our immune response against infections and tumours. Changes to T cell repertoire as we age help promote a pro-inflammatory environment which can contribute to cancer, cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes.

Precursor T cells travel from the bone marrow to the thymus, where they are matured and also taught self-tolerance, so they do not attack the body’s own cells. A population of cells called thymic epithelial cells (TEC) can produce almost all the proteins that a T cell may encounter within the body. This aids in the elimination of cells that recognising the body’s own proteins, so that T cells can help destroy pathogens but not the body’s own, healthy tissue.

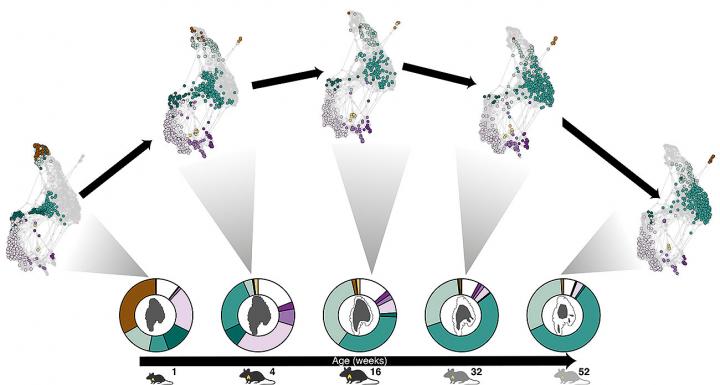

Researchers at the MRC Human Genetics Unit, University of Edinburgh with collaborators in Cambridge, Oxford and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub set out to understand how the cells of the thymus change over the course of a lifetime. Studying mice as they aged, researchers noticed that the selection of T cells became less efficient over time. In addition the T cells are not exposed to such a wide range of antigens and show a wider range of antigen-recognising receptors on their cell surface. This provides insight into the reasons that immunological function is impaired and why T cells are more likely to attack the body’s own tissue with age.

They studied cells obtained from the mouse thymus and studied both the type of cells present and the genes that were being expressed within each individual cell. As the mice aged, a group of progenitor cells – the cells that give rise to the wide range of mature TEC – were affected most by ageing. These cells increased in number, suggesting that they become stalled by the effect of ageing on the process by which they mature into their final form.

This work sheds light on how our immune systems changes with age. I hope in the long term the molecular clues from our single cell analysis give us leads to how we may promote immune tolerance and thymus regeneration

Links

- Ponting group

- Original article: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.56221

Funding from the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council.