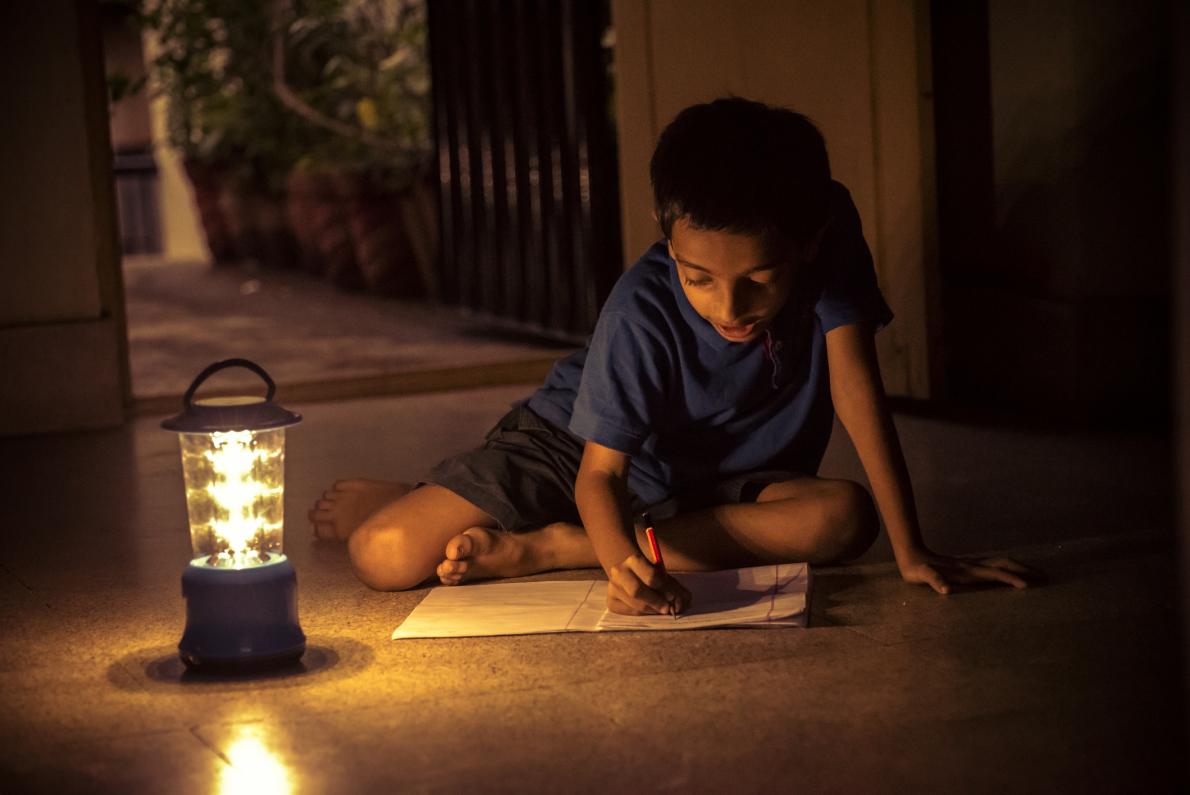

When the sun goes down in sub-Saharan Africa, almost 600 million people without access to electricity are living in the dark.

To meet these basic energy needs, solar-powered lighting technology has boomed in the last 20 years. In many parts of rural India and sub-Saharan Africa dangerous and polluting kerosene lamps have been replaced with small lanterns made out of plastic with solar panels.

“Cheap solar lanterns have become a market-based solution to energy poverty,” says Jamie Cross, Professor of Social and Economic Anthropology at the School of Social and Political Science.

However, despite expanding access to sustainable energy across the Global South, they are proving to be a short-term fix with a harmful flip side. “They are just not fit for purpose; they don’t support local economies and generate long-term waste problems,” says Cross.

Seeing the light

In 2015 with the help of students in India and Kenya, Professor Cross produced a tool to track the sustainability of solar lighting products developed for people living in South East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The ‘Off-Grid Solar Scorecard’ ranks solar-powered lanterns based on user accessibility to customer support services and spare parts, repairability and recyclability.

Cross’ team has created an online platform that contains data on the design of more than 70 solar-powered lighting devices. With this information, they were able to start a conversation with the off-grid solar industry on the importance of ensuring the sustainability of their products by ‘designing out’ waste. “There is nothing inherently sustainable about a solar-powered lamp, it has to be made sustainable – designed and produced in a way that it can be repaired,” Cross says.

Initially, their message was met with resistance. Industry insiders criticised them for being academics with ‘no skin in the game’. “I think many manufacturers were locked into design decisions and were justifying them in retrospect rather than fundamentally evaluating what they were doing, how and why,” says Cross.

In response, Cross decided to take things one-step further. With funding from the Principal’s Teaching Award Scheme, he was able to work with students at the University’s School of Design and start to investigate what a sustainable lamp would look like, challenging existing designs and addressing some of the issues their work had raised.

One of these students was Rowan Spear, now an independent circular economy consultant. As part of his Masters in Product Design, he spent a week in Nairobi, where he met solar manufacturers and saw the actual conditions in which solar lamps were used.

“I found the conflict between the mission of the off-grid sector to provide renewable energy to poor rural households and their unsustainable design practices particularly interesting,” Spear says. “Companies are not really thinking about the appropriateness of their products for the environment they are used in.”

Sustainable and repairable

After his Masters, Spear was employed to design a proof-of-concept sustainable solar lamp. He explored a wide range of materials, including cardboard, before settling on using recyclable plastic.

“We realized pretty quickly that durability is an incredibly important aspect of sustainability,” Spear says. “A product is not going to be sustainable if it falls apart straight away or doesn’t fulfil its primary function of providing light in conditions that are often quite challenging.”

Repairability was another key design feature. “Part of the problem is that solar lamps are designed and built with the assumption that the people who use them don’t have the knowledge or tools to repair them,” Cross says. Yet, in his numerous field studies he has witnessed vibrant repair economies, in which people are extremely successful at taking things apart and fixing them.

“In many places, people have access to solar panels but lack things to connect them to and charge them,” Cross says. As a result, they decided to create hand-held modular torch and an adaptor unit that can be easily connected to a solar panel, a charger and a stand. The devices are easy to take apart and run on readily available mobile phone batteries.

With the help of Cramasie, a Scottish product design consultancy, the final prototype, called Solar What?!, was formally launched at a trade event in Madrid in 2018 and all the instructions for manufacture were made available for use under a Creative Commons license.

To date, 50 Solar What?! lamps have been made in collaboration with the UK charity SolarAid and 25 have been tested in rural Zambia. Last year, Solar What?! was selected to receive an internationally recognised Design Award and the Global Off-Grid Lighting Association (GOGLA) highlighted Solar What?! to its members as an example of how to put repairability at the heart of design practices in a tool kit for managing e-waste responsibly.

“The tide is turning,” says Spear, who was at the2020 Off-Grid Solar Forum in Nairobi. “A few years ago no-one wanted to speak to us about how they tackled the end-of-life of their products. Now, they are coming up to us to tell us what they are doing to improve it.”

Carrying the torch

Campaigns around the ‘right to repair’ are gaining a lot of traction internationally and in the UK. “Solar What?! was built in that spirit, to recognise and acknowledge the right of people to repair the things that they use,” Cross says.

Cross is now working with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to help them evaluate their procurement practices. “As one of the biggest buyers of off-grid solar lighting systems for humanitarian emergencies, we are exploring how they can include repairability in the technical specifications for buying and procuring products,” he says.

The after effects of the Solar What?! project still burn bright in the partners who worked on it.

As a result of collaborating with University of Edinburgh researchers on Solar What, SolarAid has been focussing on improving the repair infrastructure and skillset in sub-Saharan Africa.

“We have set up repair centres and trained repair technicians, developed an app to troubleshoot problems and are constantly providing feedback to manufacturers, as we want them to improve the repairability of their products,” John Keane, CEO of SolarAid explains.

Speaking about his experience, Colin Crosland, Design Consultant at Cramasie Ltd, said: “Working on Solar What?! highlighted how the design choices we – and our clients – make have much wider implications that are not always fully appreciated. Since then, there has been a noticeable shift in focus towards sustainable design across all our projects”.

Picture credits: all images of Solar What?! – Solar What?!; child and lamp – shylendrahoode/Getty