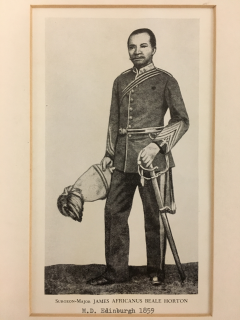

James 'Africanus' Beale Horton

James “Africanus” Beale Horton was born in Sierra Leone in 1835. He is considered Edinburgh University’s first African graduate.

By Tom Cunningham

James “Africanus” Beale Horton was born in Gloucester (Sierra Leone) in 1835. Graduating (M.D.) from Edinburgh University in 1859, he is considered

Edinburgh University’s first African graduate. A military physician, historian and political theorist; author of several books, articles and essays; founder of the Commercial Bank of West Africa; described as “a prophet of modernization in West Africa” (Ayandele, 1971) and “the first to voice national aspirations in the Gold Coast,” (Kimble, 1936) Horton had a remarkable life.

The British War Office sends students to Britain

Born to “recaptives” (both his mother and father were liberated while crossing the notorious “Middle Passage” and resettled in Sierra Leone) Horton went to the Church Missionary Society Grammar School and Fourah Bay Institute (later, Fourah Bay College). Following the British War Office’s idea to train Africans in medicine, in 1853 Horton was among the first Africans to be sent to Britain to study for a medicine degree.

As an undergraduate at King’s College London, Horton won several student prizes, and in 1858 was elected to an Associateship (Adeloye, 1976). He then moved north to Scotland to complete his medical degree. After graduating from Edinburgh in 1859, Horton published his M.D. thesis, “A Medical Topography of West Africa” before returning to Sierra Leone where he was commissioned in the British Army for service in West Africa with the rank of Staff Assistant Surgeon.

For the next twenty years he served in Gold Coast and most parts of British West Africa before retiring in 1880, at the rank of Lieutenant-General. During his military years Horton studied the history, politics, and customs of the societies of West Africa. His Political Economy of British West Africa (published in 1865) was followed by the more developed, more intricate, more polemic and better-known West African Countries and its Peoples: A Vindication of the African Race (1867). After his military career, in 1882, he launched a financial institution that he called the Commercial Bank of West Africa. He died the following year aged only 48.

The life of James “Africanus” Beale Horton has been examined by a range of scholars (Adi & Sherwood, 2003). But it is largely thanks to the work of Edinburgh Africanists George “Sam” Shepperson and Christopher Fyfe in the 1960s and 1970s that Horton is remembered today; the former’s introduction to Horton’s West African Countries and its Peoples and the latter’s biography of Horton should be sought out by anyone interested in Africanus Horton.

The first?

The story of James Horton provides an opportunity to briefly probe some aspects of the broader history of Africans in Edinburgh. Horton was one of three Fourah Bay scholars recruited to be trained in medicine in Britain as part of the British War Office’s strategy to train and employ Africans (given the high mortality rate of white British officers in West Africa). In the end only Horton and one other, William Broughton Davies, undertook the voyage. They both studied at King’s College before travelling to Scotland together to complete their degrees, with Davies undertaking his M.D. at the University of St. Andrews. Completing his degree before Horton, Davies then briefly joined his compatriot in Edinburgh before both returned to Sierra Leone (Shepperson, 1964).

Horton was not the only black student at Edinburgh at this time; he would have been contemporaries with African Americans Jesse Ewing Glasgow and Robert M Johnson (Fyfe, 1972). Indeed if “African” is extended to include people of African descent, Horton was far from the first.

William Fergusson, born in 1795 in the West Indies to an African American mother and a Scottish-settler father, enrolled on a medical degree at the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, in 1809 – apparently aged only 14 (Shepperson, 1964). After becoming a licentiate of the Royal 9 College of Surgeons of Scotland in 1813, Fergusson was posted to Sierra Leone as second surgeon to the colony. In 1845, around the time ten-year-old Horton would have been entering the Church Missionary Society Grammar School, Fergusson became governor of the colony – “the first, and last, governor of a British African colony of African descent.” (Fyfe, 2004).

Was Horton even the first African-born alumni of Edinburgh University? In a pamphlet of 1952 Captain F.W. Butt-Thompson (a colonial officer) states that John Macaulay Wilson, a Sierra Leonean Medical Officer “took his degree at Edinburgh” at the turn of the nineteenth century; (Butt-Thomson, 1952) but while this continues to be restated by scholars (Watt, 2010), Fyfe (and others who have deliberately searched for it) found no evidence to substantiate the claim (Easmon, 1961). Macaulay Wilson’s story is interesting (Iliffe, 2004). He was one of dozens of Sierra Leonean children 14 brought over to Britain during the final decade of the eighteenth century as part of the grand imperial scheme of Scotsman Rev. John Campbell to “bring over Africa to England, [to] educate her; when some, through grace and gospel, might be converted, and sent back to Africa,[…] they might help to spread civilization.” (Phillip, 1841).

Initially Campbell’s plan was to bring the children to Edinburgh. In 1796 Campbell wrote of his wish to “bring over twenty or thirty, or more, boys and girls from the coast of Guinea, through the influence of Governor [Zachary] Macaulay [of Sierra Leone]; educate them in Edinburgh [for five years], and send them back to their own country, to spread knowledge, especially Scripture knowledge.” (Phillip, 1841). Eventually the plan changed and the school was located in Clapham, London. We know from Bruce Mouser’s fascinating article on the topic that John Macaulay Wilson (Edinburgh’s first African alumni who perhaps never was) attended Clapham “African Academy.” (Mouser, 2004).

Edinburgh’s links with Africa

What all this does alert us to is that Edinburgh (and the university) has a much richer and deeper “African” history than is often appreciated. Indeed, while Horton’s life has been fairly well documented, we still know relatively little about those other Africans who immediately succeeded him in the city. This includes Derwent Hutton Ryder Waldron from Jamaica, who graduated Edinburgh in 1879 and went on to work in the Gold Coast (1881) and Lagos (1882) before studying law in London (Green, 2012).

Robert Smith, “the first African to become a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh” was born Freetown 1840 and educated at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School (Wakefield, Yorkshire) and studied medicine in Glasgow and London before completed an Edinburgh medical degree in 1872 (Cromwell, 2014). The West-Indian Samuel Jules Celestine Edwards (born circa 1857) who was neither strictly speaking “African” nor a student at Edinburgh, but whose radical Methodist preaching and campaigning in the city during the 1870s must surely be a topic that can shed light on Edinburgh’s Global-African past (Schneer, 2004).

References

Adeloye, A, 1976, Nigerian pioneer doctors and early West African politics, Nigeria Magazine, Nigeria Magazine, 3 121, pp.2-24.

Adi, H and Sherwood, M, 2003, Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa 5 and the Diaspora since 1787, Routledge, London.

Ayandele, E.A. 1971, James Africanus Beale Horton, 1835-1883: Prophet of Modernization in West Africa, African Historical Studies, 4,3 pp. 691-707.

Butt-Thomson, F.W, 1952, The First Generation of Sierra Leoneans, Government Printer, Freetown.

Cromwell, A.M, 2014, An African Victorian Feminist: The Life and Times of 19 Adelaide Smith Casely Hayford 1848-1960, Routledge.

Easmon, M.C.F, 1961, Sierra Leone Doctors of the Nineteenth Century, Eminent Sierra Leoneans in the Nineteenth Century, Department of Information for the Sierra Leone Society, Freetown.

Fyfe, C, 1972, Africanus Horton, 1835-1883: West African Scientist and Patriot, Oxford University Press, New York.

Fyfe, C, 2004, Fergusson, William (1795?–1846), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, online edn. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49294] accessed 03/08/16

Green, J, 2012, Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914, Routledge.

Kimble, D, 1963, A Political History of Ghana: the Rise of Gold Coast Nationalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Mouser, B.L, 2004, African academy—Clapham 1799–1806, History of Education, 33, pp87-103.

Phillip, R, 1841, The Life, Times, and Missionary Enterprises of the Rev. John Campbell, London

Schneer, J, 2004, An African Victorian Feminist: The Life and Times of 19 Adelaide Smith Casely Hayford 1848-1960, Oxford Dictionary of 20 National Biography, Oxford University Press, online edn. [http:// www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/71088], accessed 03/08/16.

Shepperson, G, 1964, James Africanus Beale Horton, West African Countries and Peoples, Edinburgh.

Watt, J, 2010, Poisoned Lives: The Regency Poet Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L.E.L.) and British Gold Coast Administrator George Maclean, Sussex Academic Press.