What you did next

It’s not unusual for What You Did Next to feature an Edinburgh graduate who is a luminary in his or her field. But Alison Kinnaird fits that bill twice over.

Alison Kinnaird’s name appears in lists of leading lights in two separate creative spheres: her glass engraving can be seen in collections across the globe, and she has led a revival of traditional Scottish harp music through her research, writing, performance and recording.

Both branches of her story reveal a tenacious determination to explore the avenues that most fire her enthusiasm, and both have been catalysed by her experiences as a student at Edinburgh.

Alison was a talented cellist as a girl, and was once advised to consider going to music school to study the instrument. “But I wasn’t really dedicated enough,” she says. The classical genre “was not really my music”.

People said only a few harp tunes survived, but I thought ‘good grief it was played for more than 2,000 years’.

She heard a girl playing the Scottish harp at a Saturday morning orchestra practice, “and that was it”, she recalls. The girl’s teacher was Jean Campbell, and Alison soon began studying with Campbell herself.

But Alison says the harp at that time was “a drawing room instrument”, its true tradition having died out at the end of the 18th century. It wasn’t until she began her studies at University that Alison learned of that tradition and became determined to rekindle its embers.

As a Celtic Studies and Archaeology undergraduate, she studied under Professor William Matheson, who at the time was writing a book about the “Blind Harper”, a celebrated 17th century Gaelic poet and musician. “He was very happy to talk about the harp to someone who was interested,” Alison says. “Matheson was a great tradition-bearer himself – he knew so much in the oral tradition. We used to go to his flat in the evenings and he would start singing. He knew hundreds of songs. Eventually he recorded many of them for the University’s School of Scottish Studies.”

Alison became convinced that there must be something remaining of the earlier tradition. “People said only a few harp tunes survived, but I thought ‘good grief it was played for more than 2,000 years’.

“I began to do a lot of research at the University library, finding harp-related material. I was also playing the harp while at University and I was introduced to a wide circle of people who were interested in traditional music.”

By 1978 Alison had recorded the first album of Scottish harp music, 'The Harp Key - Crann nan Teud', which has since been essential listening for anyone interested in the instrument. She went on to co-author the first book on the Scottish harrp, 'The Tree of Strings', in 1992.

Alison and her husband, the musician Robin Morton, have played a role in a wider revival of traditional music. Thanks in large part to her work, today the Scottish harp is a popular instrument and can be heard at traditional music events across Scotland and elsewhere.

Scottish Harp or Clàrsach?

Alison Kinnaird is careful to talk about the “Scottish harp” rather than use the often-heard Gaelic term clàrsach.

She plays both, but explains that the true clàrsach is a different instrument from what many people may mean when they use the word. A true clàrsach has metal strings, whereas the more commonly played harp – the harp of the east coast and lowlands – has gut strings, which today are often made of nylon.

Playing the two instruments requires different techniques: the metal strings of the clàrsach are plucked with fingernails, while gut-strung harps are played with the pads of the fingertips.

“They’re related but very different,” says Alison. “You could be good at one but not the other. It’s a bit like the piano and organ.”

While making her musical discoveries, Alison had a second chance encounter that would change her life. In the summer break before her final year at university, she spent a holiday with her parents in Forres, Moray, where her father’s family had come from.

“It was a wet day and there was an article about a glass engraver, Harold Gordon, in the local paper and we went to visit his studio. He saw some drawings that I’d been doing, and he said, ‘You ought to try this’ and I immediately got hooked. I went to work with him for the summer.”

On returning to her studies, Alison sought out Helen Turner, then Head of Glass at Edinburgh College of Art, who said she could use the glass department’s equipment to hone her skills. “I decided that was really where I wanted to go,” Alison recalls.

She launched her glass career in a shed in her parents’ garden, where she initially engraved items such as bowls, as gifts for family and friends. Today she works in a small studio in her home in Midlothian, a converted church with tall windows that flood her workspace in light.

Her work is constantly evolving – as with the harp, Alison has developed the medium through perfecting old techniques and pioneering new ones.

A new direction for her work came in 2002 when she received a Creative Scotland Award from the Scottish Arts Council, which she says “effectively gave me a year to experiment”. The resulting work, 'Psalmsong', introduced new scale, and a new approach to lighting.

Alison’s traditional lathe method (see “The wheel that cuts”, below) limits the size of works that can be produced. But for Psalmsong she used multiple layered sheets to produce a work three metres in length.

Lighting in galleries and museums can also be a challenge. “They tend to put glass in a showcase because it’s fragile, with a spotlight at the front, and it just kills the glass, which has to have light coming through it,” Alison explains. For 'Psalmsong', she experimented with coloured lighting, and the final work is lit with fibre optics, which shine vertically through the glass, perfectly colouring the engraving.

When 'Psalmsong' was first displayed, it was seen by the Director of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, who immediately sought the work on loan. After a year at the V&A, 'Psalmsong' is now on permanent display at the Scottish Parliament.

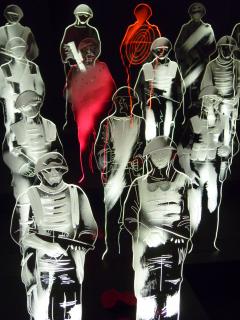

Today Alison produces works that include their own LED lighting. “This way I can send glass off on show and know that it’s going to look OK,” she says. An example is her recent work 'Unknown', a response to war depicting 52 soldiers, which is currently on a two-year tour of Scotland.

Another challenge of scale came in 2011, with a commission to make a new Donor Window for the Scottish National Portrait Gallery to be displayed on its reopening after major refurbishment in 2011. The window consists of portraits and floral designs in 26 roundels, filling two neo-gothic arched stone frames and a round window at their apex.

And Alison’s work is now moving in yet another direction. She is embarking on a commission for a private collector in Beverly Hills. Like the Donor Window, the work will be around three metres tall, but this time it will be on a single sheet of glass, not a series of small panels.

For this, the traditional small lathe is useless, and Alison will instead use engraving wheels connected to a “flexible drive”. She will take up residency in specialist studios in Germany. With an undimmed enthusiasm for exploration, she says: “It’s exciting. It’s always a little bit daunting when you tackle something new, but in the past it’s always worked out.”

The wheel that cuts

Using the ancient intaglio technique, Alison’s main engraving tool is a tiny lathe from which a spinning wheel sticks out on a spindle. She brings glass up to the wheel and achieves the marks she wants by moving the glass.

Diamond-edged wheels do the rough work, copper wheels the more detailed stages. Alison feeds the copper wheel with water and carborundum, a silicon carbide powder. This does the actual cutting, wearing away both the glass and the copper, which needs regular filing to rebuild the desired cutting profile. Near her lathe is a rack of wheels of varying sizes – all steadily shrinking with use. The lathe spindle reaches only 20cm, so for larger works Alison uses a wheel on a flexible hand-held drive, similar to a dentist’s drill.

Send us your news

We'd love to hear from alumni on your experiences.