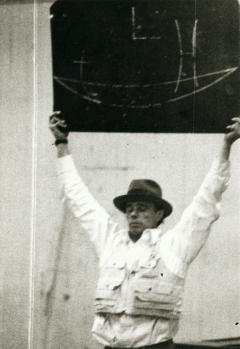

6. Joseph Beuys holding up a blackboard during his performance event Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, in studio C.08

Beuys’s mesmerising performance was inspired by his experience of the Highlands and was something between a requiem and paean to his cultural predecessors.

Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony was an ‘action’, a collaboration between Joseph Beuys and the Danish Fluxus composer Henning Christiansen.

Beuys's symphony of art

It was inspired by Beuys’s experiences of Scotland during the long summer of 1970. In some ways it was a response to Felix Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture (Fingal’s Cave) of 1830, a Romantic composition Beuys knew well, but found too sentimental.

Beuys’s performance was accompanied by a film of Rannoch Moor that he had made on 13 August 1970. In this respect, it was also a collaboration with Demarco, who was responsible for enthusiastically guiding Beuys to these sites in the first place.

In November 1970, Alastair Mackintosh gave a first-hand account of the original ‘action’, performed ten times over five days at ECA:

The room was large, a studio in the college, the lighting drab with neon […] His actions are reduced to a minimum: he scribbles on a board and pushes it around the floor with a stick in a 40-minute circuit of Christiansen; shows films of events by himself (not entirely successful as the editing destroys the rhythm), and of Rannoch Moor drifting slowly past the camera at about 3 mph. He spends something over an hour and a half taking bits of gelatine off the walls and putting them onto a tray which he empties over his head in a convulsive movement. Finally he stand still for 40 minutes. Thus told it sounds like nothing; in fact it is electrifying.

During this performance, Beuys attached three pieces of paper to the gelatine-covered wall of the ECA life room.

On the first piece of paper, it was written, ‘Where are the souls of …?’

On the second piece of paper were the names of artists who were being taken ‘seriously into account’ by Beuys:

Naturally there was the name Malevich, summing up the Russian avant-garde, Van Gogh, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, and God knows how many others. I was surprised that some of the other names were more from the history of ideas, the history of civilisation. I realised this was a kind of requiem.

Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony was to have an impact well beyond ECA when a variation of it, entitled Celtic +~~~, was performed by Beuys, again working with Christiansen, at the Zivilschutzräume in Basel on 5 April 1971.

Photographs by Ute Klophaus of Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony at ECA appeared in a visual essay compiled by Johannes Stüttgen for the fifth issue of the important German art magazine Interfunktionen (1970).

Later, the ‘action’ was canonised in the catalogue for the major New York Guggenheim retrospective Joseph Beuys (1979), curated by Caroline Tisdall, with Beuys’s contribution to SGA given nine pages of coverage in terms of photos and text, the latter mostly drawn from Mackintosh’s Art and Artists article cited above.

C.W.