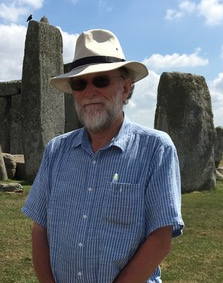

Tribute and obituary for Professor Richard Carter

Professor Richard Carter, a world-leader in the biology of malaria parasites, died aged 76 on the 4th September 2021.

Many areas of modern malaria research rest on Richard’s insight, talent, and dedication to his research which included three major paradigm shifts in malaria research over four decades.

Richard came to Edinburgh in the 1960s as a student, using his training in biochemistry to initiate studies on the genetics of malaria parasites. At that time there was general unease about “what could genetics be useful for”?

Richard, alongside David Walliker and Geoffrey Beale, unequivocally demonstrated its utility and provided the foundations on which the field of parasite genetics is built.

For example, by identifying genetic markers and studying diversity, Richard’s work revealed important fundamentals about processes involved in the malaria parasite’s life cycle as well as how it evades death from immune responses and drugs.

During a spell working in the USA, Richard honed his skills as a parasitologist, developing an important interest in the mating biology of parasites. Many firsts can be attributable to Richard’s technical skills, which were often based on taking the parasites’ perspective on life coupled with his interest in all forms of biology.

Richard was also a remarkable repository of knowledge and this coupled with his deep curiosity and broad interests meant that a visit to his office was never dull.

When going to his office to ask for an opinion or to find out a fact, one never knew what twists and turns the conversation would take. Usually though, Richard would furnish you with far more information than you expected, having gently revealed that you were not asking the right question in the first place.

His rare ability to see through the dogma meant that Richard’s views were sometimes highly controversial but often correct. For example, recent work has overturned the conventional wisdom about the origins of human malaria parasites, proving Richard’s intuition of several decade ago to be on the money, and resulting in a species being named in his honour.

His ability to marry natural history with medical applications gave him the idea that certain kinds of immune responses could prevent parasites from infecting mosquitoes and so, the field of “transmission blocking immunity” began. Now, several decades on, transmission blocking interventions are gaining great traction.

During his long and illustrious career that ended with retirement in 2010, Richard was a kind and generous colleague and mentor. He never tired of wearing a lab coat and maintained a healthy disrespect for the academic establishment, with little interest in the metrics that rule career progression.

Yet, he saw the potential in everyone and instilled the skills to succeed in the students and staff that he worked with, many of whom have become leaders in malariology. Richard also cared deeply about people, in his lab and beyond, always guiding students to follow their own interests whilst challenging their ideas when necessary.

Even after retirement, Richard proved a committed mentor for the next generation of researchers under his wing. Richard was also a historian of malaria research; his memoirs on the development of the ideas underpinning malaria genetics and transmission blocking immunity are both highly illuminating and enjoyable to read.

Beyond the world of malaria, Richard cared deeply about social and environmental justice for all future generations. A family man, he enjoyed sharing his interest in history and the natural world with his children, grandchildren, and wider family.

A talented pianist and watercolourist, he also loved making things, ranging from garden fish ponds to stuffed felt animals, model ships and cardboard volcanos. In Edinburgh he was also an enthusiastic "guerrilla" gardener!